“One of the translations for ‘takesa’ is ‘prideful.’ We’re proud we’re putting our residents in a safe, happy community.”

Debbi Hammond’s pride is palpable. She was the first-ever president of the board of Takesa Village in Mead, Washington. The manufactured home community where she’s lived for six years is the first resident-owned community of its kind in Eastern Washington—and it’s where she and her neighbors are proving it really does take a village.

Subject to an absentee landlord, residents of this mobile home community lacked safety, security and belonging. Debbi Hammond worked tirelessly to rally her neighbors to form a housing cooperative and purchase the land their homes sit on.

Formerly Mead Royale Mobile Home Park, Takesa Village sits 20 minutes north of Spokane. Residents came to this 43-acre park for many reasons. Hammond wanted to be farther from the city and closer to her son and grandchildren. Jerry and Esther Feltman wanted a home base that was equal distance between children, grandchildren and other family in Montana, Western Washington and Canada. After retiring and suddenly becoming a widow, Cindy Knorr found it affordable. She also hoped she’d find neighborly activities and companionship here. Diane Pippen was searching for a long-term rental where she could raise five kids without worrying about moving frequently.

But what these folks found was not an idyllic spot to settle down in the Inland Northwest. Overshadowed by high crime rates, they found a neighborhood in a constant struggle with drugs, prostitution, squatters and nuisance houses.

“People called it ‘Meth Royale.’ It was miserable,” says Pippen.

After residents formed their Takesa Village cooperative, it became a true community where neighbors pitched in and kids were free to play outside.

While many residents owned their homes, the landlord owned the land. Management controlled rent, water, electric and wastewater systems. They also decided what, if any, repairs and improvements were made to the roads, grounds and the community.

Residents had no sense of safety, security or belonging. They were discouraged from going outside; children weren’t permitted to ride bikes or splash in a kiddie pool. No one trusted or spoke to his or her neighbors. Most lived in isolation, filled with insecurity, fear and the constant threat of eviction. Even the office was off-limits. Renters say management wouldn’t take calls and wouldn’t take action.

When they learned that the Mead Royale property was being put up for sale, concerns about their future only grew. Feeling rejected, defeated and forgotten had become a way of life.

Prior to the efforts of Hammond and her neighbors, the property had fallen into such disrepair that many residents had begun packing their belongings and looking for other places to live.

After living in Mead Royale for 23 years, the Feltmans packed their boxes and got ready to relocate. But for many families in the park who live in extreme poverty, moving out was not an option. So with no one on their side to help, demoralized residents set out to help themselves.

“I thought, ‘There has to be something we can do. There has to be a better way,’” Hammond says. “It sounds like a movie, but under a cloak of darkness, a group of us met in the tiny kitchen of a nearby church.” And an idea took off from there.

Taking Control through Action—One Step at a Time

“We wanted to see where we could go from nowhere,” Pippen recalls. “We were knocking on doors, posting fliers and raising money to get snacks for meetings so people would want to come.”

Building trust wasn’t easy, says Pippen. “I had to get my foot in the door to help them understand we’re doing this to save our homes and save what we could potentially leave our children in 10 or 20 years.”

Under what they described as a “movie-like cloak of darkness,” Hammond and her neighbors met in a tiny kitchen of a nearby church to formulate a plan for taking back their community.

The group made phone calls, asked questions and met with experts. Hammond reached out to ROC Northwest, an affiliate of ROC USA, a nonprofit organization that works to facilitate resident ownership of manufactured home communities. Program Director Matt Fast met with residents to talk about options.

Fast explained the benefits and responsibilities of forming a legal, functional cooperative corporation. First, this would allow the corporation—not individuals—to apply for a loan to buy the property. It would also make each household eligible to become a member of the cooperative, and together, they could manage the community as a business. As a resident-owned community, or ROC, each member household would have equal ownership in the property and equal say in how the community is run.

Residents would continue to own their own homes as well as a share of the corporation that owns the land. They would govern themselves and elect community leaders from within. They would collaborate and vote on how things should be run rather than waiting on someone from the outside to make changes for them.

After witnessing his community deteriorate over 23 years, Jerry Feltman and his wife had packed their boxes and got ready to relocate. That all changed once he worked with his neighbors to form a housing cooperative.

Each member of the co-op would have a say in decisions that affected his or her security. Their new board would set the eviction process policies and write the screening procedures for new applicants. They’d also have control of the rent, repairs, improvement projects and community rules. And, the way the company would be set up, any excess revenue would go directly back into the community.

For ROC USA to help them incorporate as a cooperative Fast said at least 51% of households needed to vote in favor of the idea. At Mead Royale, nearly two-thirds of the households attended a community meeting and voted unanimously to explore becoming a ROC. The membership share ($200) in the new company and the initial down payment toward that share—known as the joining fee—were also set by popular vote. Neighbors worked together to raise funds for those who couldn’t afford the joining fee. Fast took the community’s enthusiasm and willingness to put in its own money as signs it was dedicated to moving forward.

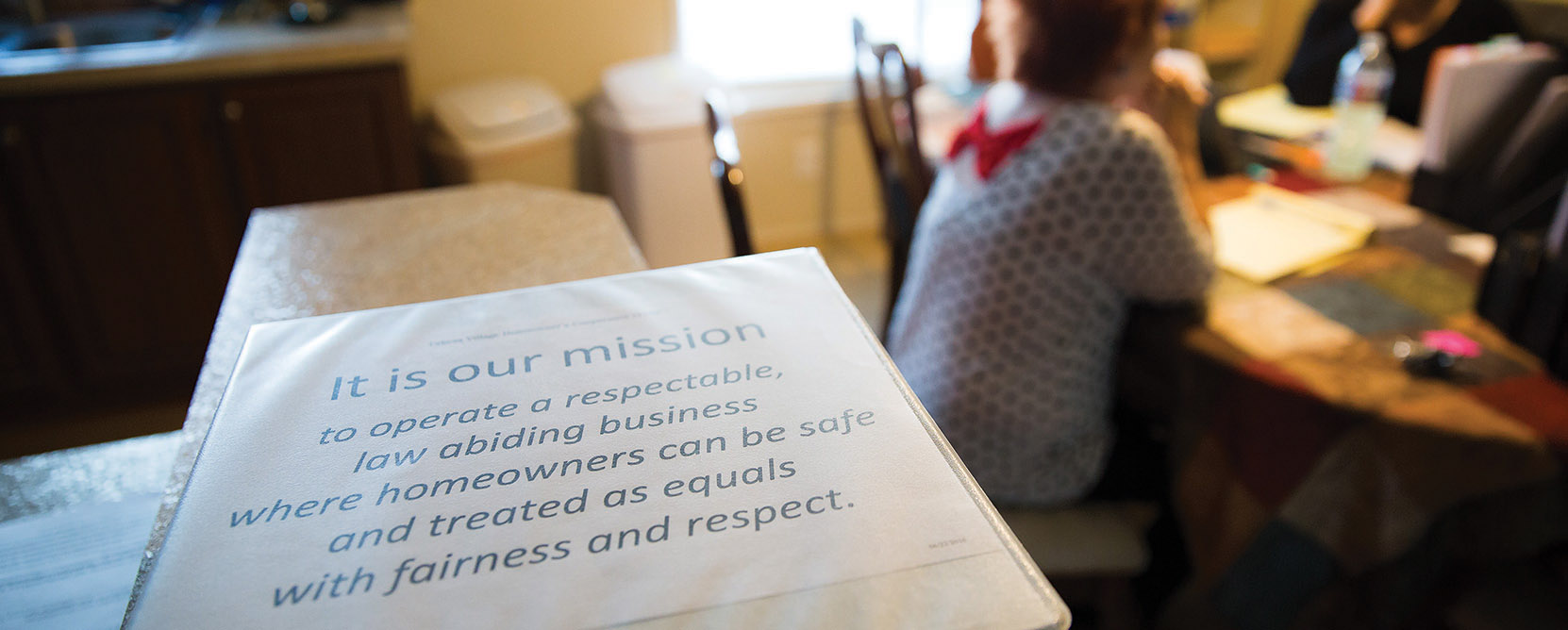

As a resident-owned community, or ROC, each household has equal ownership in the property and equal say in how the community is run.

“They were building their own history and their own story, and that’s exactly what we want,” says Fast. “When there’s a personal stake in the narrative, when people identify personally with it, they have a real sense of ownership.”

Becoming a ROC is a big step and one that involves a lot of training, according to Fast. The first part of that training is helping member-owners understand the process of applying for funding. “People want to talk about financing options, but they aren’t sure how to go about it,” he says. “While certainly achievable, the logistics of commercial property transactions can be daunting to homeowners who’ve never been through a multi-million-dollar purchase before.”

With technical assistance from ROC USA, and financing from Capital Impact, owners of the 149 households seized “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” and purchased the property.

He explained to the newly formed Takesa Village Homeowners Cooperative, Inc. that the process would involve engineers, surveyors, attorneys, environmental assessments and more. And, he said, a typical commercial property lender expects 25% down. For Takesa’s members, that would have been in the millions. “If you aren’t sure whether you can afford to go to school or repair your car, you’re not going to have a million or so dollars hanging around—even if it is divided among 149 households.” Without a different way to finance the deal, it would have been a deal-breaker.

Finding Additional Support from Outside the Village

That’s when ROC USA reached out to Capital Impact Partners to partner in financing the deal along with the Washington Housing Finance Commission. As a mission-driven lender, CIP has worked with and financed ROC communities in other parts of the country.

“It was apparent that the impact of this project would be significant in that it would add to the permanent supply of affordable housing options in eastern Washington State,” says Estee Segal, Loan Officer at Capital Impact Partners. “In addition, supporting the cooperative model of land ownership aligns with our mission in that it gives residents more control over their futures and helps to build stronger communities.”

And so, with ongoing operational support, guidance and training and financing from ROC USA Capital and Capital Impact Partners,149 households seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and purchased the property. Through determination, teamwork and education, the newly formed cooperative corporation took ownership on May 2, 2016 and rechristened their community “Takesa Village.”

Soon after purchasing the property, residents christened their community with a new name and a new sign.

“Normally a business has owners who manage the business. Ours has a board of directors,” Hammond explains. ”Homeowners give us direction on what we want to do.”

The first thing they did was vote out management and maintenance. They held community meetings, went over budgets and talked about resident concerns.

“We asked, ‘What do you want to see done?’” says Pippen, then social chair of the board. “We were getting their input and making them understand they have a say…. It matters to us when it didn’t before.”

They organized all-volunteer committees and got to work. With chainsaws, rakes, mowers and blowers, they cleared brush, limbs, leaves and debris from empty lots and common areas. A giant dumpster was filled with trash in just five hours. Drywells were serviced and lakes of standing water were drained from roadways. The sewer system was upgraded, a swimming pool was repaired and a new pump house built.

All-volunteer committees keep the community clean and take care of major repairs like the swimming pool and sewer system.

“It’s a learning experience for everyone,” says Knorr. “I believe in Takesa. It takes a village…We’ve all got to do this together.”

The Feltmans decided they wanted to continue to be part of the change. They’re buying a double wide and staying. “It’s 100% different and still getting better,” Jerry says.

These residents are transforming their community and its reputation. They’re working with law enforcement and firefighters to build more positive relationships. Veterans volunteer time to patrol the grounds. Squatters are disappearing, and drug activity and nuisance neighbors are on their way out.

“Everybody watches out for everybody,” says Pippen. “It’s definitely changed from a frozen-over state to really warm and caring people.”

The newly cleaned clubhouse is now a hub for social events and community meetings, with a small library of books and donated laptops.

In the newly cleaned clubhouse, neighbors get together for social events and community meetings. There’s even a small library with books, puzzles and games. With donated laptops, students have internet access, and tutors are available to help with homework.

“We’re really excited,” Hammond says. “We can give our kids something other than a life of crime or life of drugs.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK